Harvest Season

THE ART OF SEA SALT

Île De Ré, France

Scroll to explore

The Story

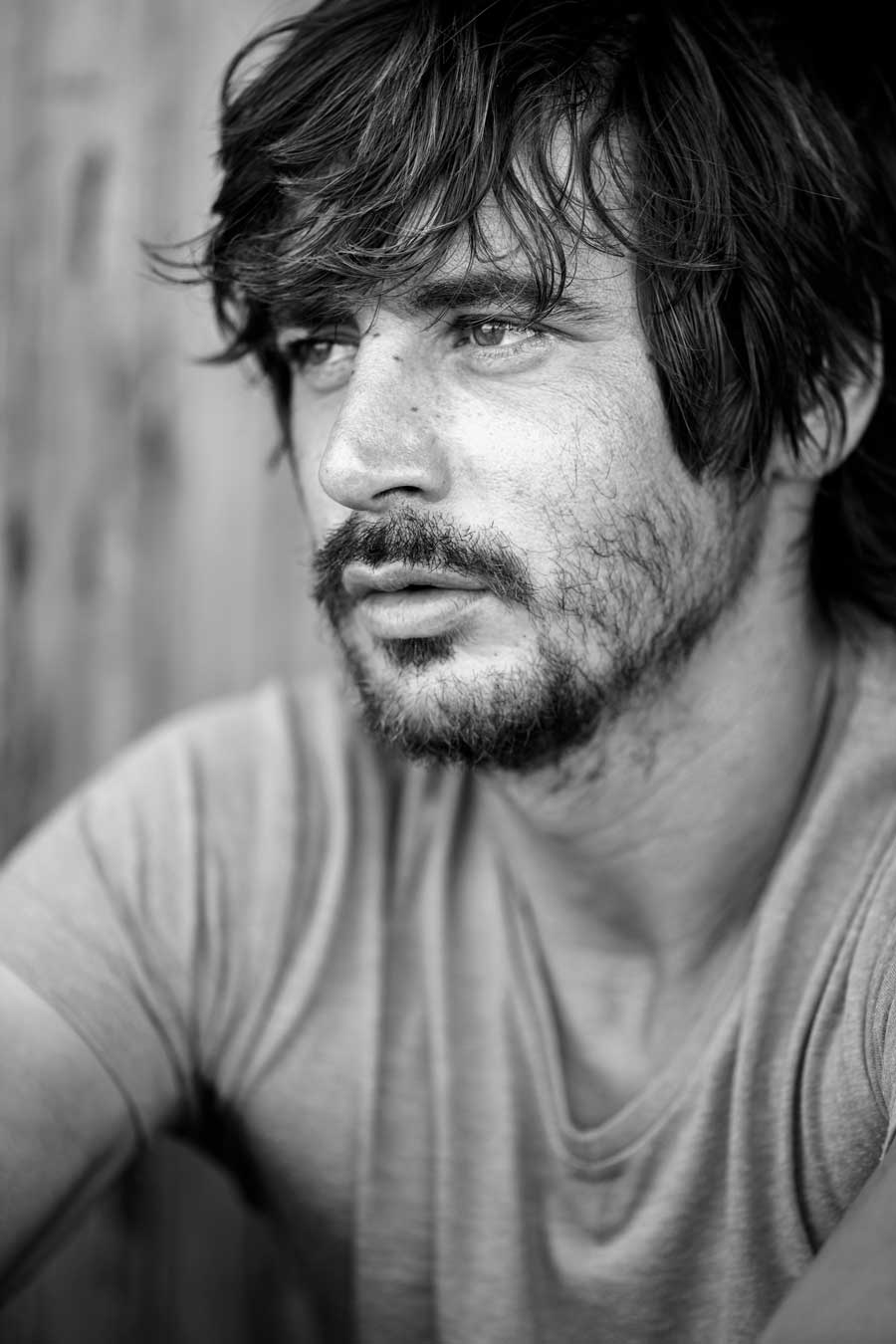

A Conversation With Brice Collonier

Saunier on Île de Ré

Brice Collonier is a saunier, or salt worker, collecting salt on the French island of Île de Ré in a tradition that dates back to the twelfth century when it was introduced by Cistercian monks.

Brice is amongst a new generation of salt workers that have rediscovered this craft that was nearly abandoned on the isle. He carves and reshapes the landscape continually, according to the winds and temperature, resulting in the cultivation of two natural, hand-crafted products - the highly nutritive, grey-hued gros sel and the rich in flavor, pure white fleur de sel.

We had to rediscover this area like archeologists, because everything was still there, but hidden under the mud.

Brice Collonier, Saunier

S+O — WHAT IS THE HISTORY OF SALT HARVESTING ON ÎLE DE RÉ?

COLLONIER — The first salt marshes on Île de Ré were created during the Middle Ages to preserve food. At that time, there were marshes all over the French coast where this clay was found naturally.

The salt marshes were acquired from the sea. The ancient, salt harvesters modified dykes to dry up the big troughs of mud that were revealed during low tide. The ground was impermeable, making it possible for water to circulate without disappearing into the ground by infiltration.

The ancient craft prospered until really the nineteenth century when the salt marshes started to decline in comparison to other systems, industrial systems, which came to replace the traditional methods of harvesting salt.

The salt workers didn’t really know how to adapt because our work is extremely manual and the terrain was clay-like which made it quite difficult for machines to access. The overall process was very hard to mechanize, so it was abandoned.

S+O — WHEN DID THE MOVEMENT TO RESURRECT THE TRADITION OF SALT HARVESTING ON THE ISLAND START?

COLLONIER — The older sauniers continued really their profession out of pure passion. It was part of their family history. They were born on the island and were taught salt harvesting when they were young. But they could no longer do it professionally, as the money to be made was quite limited.

In the nineties, people from other parts of France started to arrive with an interest in rediscovering the craft. These people came from different walks of life, very few from rural regions, but were attracted to a certain lifestyle which required a lot of work and the possibility of offering a high-quality product.

It was practically a godsend, given that the profession had been abandoned. We had to rediscover this area like archeologists. Everything was still there, but hidden under the mud.

Nowadays there are sixty of us working together and we have established the cooperative, Les Sauniers de l' Île de Ré.

S+O — DO YOU BELIEVE THAT WANING INTEREST IN THE TRADITION PUT THE YOUNGER SAUNIERS OF ÎLE DE RÉ AT A DISADVANTAGE TO OTHER SALT HARVESTERS AROUND THE WORLD?

COLLONIER — It is true that, in a certain manner, we were influenced by the demise of the craft. We were missing valuable, precise information about the particular methods used here in the past.

There is another place, further north in France, called Guérande where the tradition was preserved. There are obvious advantages to having the knowledge, but at the same time I believe tradition can hold us back.

We were obliged to reinvent the know-how because we no longer had elders to teach us their methods on the island. I am quite lucky to have arrived into a territory where you had the liberty to create something. To be able to take an abandoned marsh and reshape it literally from the ground up, while respecting the past as much as possible, but to invent something, was what I’ve always dreamed of doing.

The marsh I work on today was abandoned almost fifty years ago. As such, I learn many things every year and continually acquire the knowledge, so that I can truly call myself a salt worker. First of all, I’ve learned that one needs to really remain humble. It’s a profession of eternal learning.

S+O — WHAT INITIALLY ATTRACTED YOU TO THIS PROFESSION?

COLLONIER — I first worked in the marshes as a summer job. I was at university, studying Architecture and Fine Arts. I was asking myself a lot of questions back then. Questions I was able to answer here in the marshes. The experimentation involved the participation of nature and art. It’s the way one works with the ground and with the environment.

My attention was drawn to the natural landscape. I was quite sensitive to this because, when you study art, you are always confined to particular spaces. The galleries, even the museums, are usually located in urban places. But here, on Île de Ré, I love the vast, experimental terrain and that nature makes sure everything is in place.

S+O — WHAT SUSTAINS THIS ATTRACTION NOW?

COLLONIER — It's a profession that’s really very close to nature, not only because we are in the fields throughout the day, but because it is very much linked to the sensitivities of the weather. It’s true that we only work when the weather is good..

Everything here is balanced. We work alone in our salt marshes. There’s something that attracted me to having this kind of liberty. The liberty to work at my own pace and the sun’s pace.

I have a cabin which is more of a refuge where I meet with colleagues and members of the cooperative. We gather together and share our experiences. The economic aspect unites us, but we work alone most of the time but in total solidarity.

S+O — WHAT TYPE OF SALT IS HARVESTED ON ÎLE DE RÉ?

COLLONIER — We harvest two types of salt - a coarse salt known as gros sel and fleur de sel.

The coarse salt is characterized by large crystals which are slightly tinted grey because they take the color of the clay on which they appear. This salt forms on the bottom of the basins. Sauniers make waves on the water with their tools, bringing the salt grains to the surface to collect them. During harvest, I can produce nearly forty kilos every two days.

The fleur de sel is a rare product that forms on the surface of the water in the basins. Tiny crystals emerge and form a fine crust of the purest white salt. The conditions needed are way more demanding. It requires the water to be quite salty and the temperature of the water to be quite high. There must be a certain type of wind dominant, not too weak not too strong.

S+O — HOW WOULD YOU DESCRIBE THE DIFFERENCES BETWEEN THE TWO SALTS?

COLLONIER — The coarse salt is more interesting from a nutritional standpoint because it contains more minerals due to the characteristics of the clay. It is great to use in the kitchen. Its taste is typically softer, subtler, but this also depends on the harvest.

The fleur de sel, on the other hand, is a purer salt consisting of smaller crystals which typically have a more explosive taste in the mouth. It tastes better on the palate, and is a salt that is actually used, with the help of the fingers, to sprinkle on food as a finishing touch.

S+O — WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE PRODUCT FROM ÎLE DE RÉ VERSUS OTHER SALTS?

COLLONIER — There is an enormous variety of salt in the world. It can be found under rocks, in salt mines, in lakes, or be fossilized. However, the particularity of the salt in Île de Ré is that it is harvested in a completely natural way as was done historically in France, which is to say that the process is mechanized to the barest minimum.

The advantage of this type of salt production is that it does not need any form of additional industrial process to make it fit for consumption which is the case for many kinds of salt nowadays. They need extra products added to them so that they can be rich enough in nutrients.

Our salt is expensive compared to imported salt from mines or industrial salt. It’s a product that’s undergone a lot of transformation. The texture, the taste and the way it is produced. It is not an easy job.

Many people don’t know exactly how it is harvested, but they are willing to spend a little more money if they know that it is made using traditional methods.

S+O — WHAT IS INVOLVED IN A TYPICAL HARVEST SEASON?

COLLONIER — In reality, a saunier’s job starts in the month of February. The entire landscape of the marsh, made of natural clay and seawater, must be drained separately, and allowed to breathe. We remove the mud and push it along the border of the basins to build and reinforce the structure of the marsh. This protective layer of mud is an important part of the preparation which fortifies the entire marsh for the upcoming season.

The harvest lasts on average around three months. It starts at the end of May, or beginning of June, and it goes until September. Of course, it varies wildly according to the weather. Overall, it’s a short period of time but there’s a lot of hard, physical work. Especially for those of us who were not born with a tool in our hand.

We rest after September. The days are shorter, the humidity increases with a lot of rain, so the marsh is no longer able to produce salt.

S+O — AND A HARVEST DAY?

COLLONIER — All the days are really interesting on the salt marsh. The day starts quite early. We are on the coast, so the wind comes in gently from one direction during the morning, and stops at midday. There is a calmness. And then in the afternoon, the marine breezes will start blowing again. The wind returns at around three or four in the afternoon, and it creates a certain rhythm.

Fleur de sel will form or not, according to the winds. If it does form, it will appear around five o’clock in the afternoon, and must be harvested very quickly so that it doesn’t float to the bottom. The quantity of salt is determined every day by each individual cloud or each ray of sunlight. It’s a very interesting aspect of this work which can be really difficult sometimes, given that it’s not easy to plan your life each day.

The daily satisfaction that we have varies depending on the end product. If we are lucky to have really white salt, we can say "beautiful harvest today", or that the fleur de sel was really fine today. It’s still a mineral, a salt. It’s nutritive, but it's almost something as precious as jewelry. Every time we stir the clay, we are always remodeling the landscape. So it's more like forging a sculpture, or creating jewelry. This is what makes it so satisfying.

The quantity of salt is determined every day by each individual cloud or each ray of sunlight.

S+O — WHAT IS YOUR RELATIONSHIP WITH THE ECOSYSTEM OF THE ISLAND?

COLLONIER — This part of the sea has been dried since the twelfth century. It’s an agricultural process, but not an agricultural exploitation of the ground. The land that we reclaimed from the sea in order to work, has been protected since the nineteen-sixties when the French government registered it as a reserve. The state bought the marshes to preserve the biodiversity, and specifically protect the bird colonies in the area.

The work we do in the salt marshes helps circulating the water which is healthy for the environment, and attracts the migrating birds. We create the little inlets where they come to make their nests, and perch in the spring. We all work together. Much of our work on the land focuses not only on the harvest preparation, but also on the protection of the birds.

And maybe when people buy the coarse salt or fleur de sel from Île de Ré, it somehow guarantees the preservation of all these ecosystems.

S+O — WHAT IS THE BIGGEST THREAT TO THIS PROFESSION IN THE FUTURE?

COLLONIER — Perhaps climate change. Our archives show that the weather can fluctuate wildly on the island. There is a testimony, in the form of a poem, from the Middle Ages that says that salt was stored on the highest hills to keep the harvest from being lost when the sea overtook the landscape and broke the dykes.

Five years ago there was a storm on Île de Ré and the dykes gave way. All the salt marshes were filled with seawater which is natural to them, but the actual damage caused by the violence of the water entering the marshes was so much that a lot of work was required afterwards in order to restore the marshes and island overall.

I was more fascinated at the time than distraught. It was really amazing to see nature at work, even when it gets upset and goes wild. It is a landscape that’s always changing. We’ll learn to live with it, if it happens again. If we start to worry or become wary, we’ll lose the relationship that we should foster with nature. We should always continue to love it.

Every time we stir the clay, we are always remodeling the landscape. So it's more like forging a sculpture or creating jewelry.

Credits

Photography by Brian Sokol

Film by K23 Films

Special Acknowledgments - Île de Ré Tourisme and Coopérative des Sauniers de l'Île de Ré

The Objects

Exclusive Edition 001 Sel De Mer

This crunchy sea salt is hand-harvested using ancient methods by the cooperative, Les Sauniers de l'Île de Ré. The first salt marshes on Île de Ré were created during the Middle Ages to preserve food. At that time, marshes could be seen throughout the coastline where the clay used to form the marais was naturally found. Today, there are sixty sauniers harvesting fleur de sel and gros sel within the island cooperative. Available only through Stories + Objects, the Île de Ré sel de mer comes with a hand-thrown, hand-painted porcelain salt jar by master ceramicist Roberto Carrillo.

The Destination

Île De Ré, France

Île de Ré is a small island located on the west coast of France two miles off the coast of La Rochelle in the Poitou-Charentes region. Originally an archipelago consisting of a few small islands brought together by silage and the formation of the salt marshes, Île de Ré’s abundant waters and soil means that local markets and restaurants are stocked year-round, not only with salt, but with locally cultivated potatoes, wine and oysters that are harvested at low tide off shore. The idyllic weather and charming villages make the island a favored destination for chic Parisians and nature enthusiasts alike.